One of my very earliest posts addressed a very basic problem in the study of microscopic organisms: knowing the identify of whatever you are looking at (see “All exact science is dominated by the idea of approximation …”). The germ for this post came from a quotation from Bertrand Russell that said that, when you counted anything, you had a good idea of what constituted whatever it was you were counting. If you were counting oranges, you knew to exclude apples, obviously, but also tangerines and satsumas, which may look similar but are genetically-distinct. That’s not always so straightforward for microscopic algae, as I’ve discussed in many posts, but it is a core, largely unspoken, assumption. I’ve also emphasised the distinction between the sciences of taxonomy and systematics, and the craft of identification (see “Disagreeable distinctions …” and, more recently, “How to identify diatoms from their girdle views …”). As an ecologist, I need to use the outputs from taxonomy but, at the same time, I am constrained by time, equipment and, indeed, by the knowledge that I can readily access, in my ability to do this.

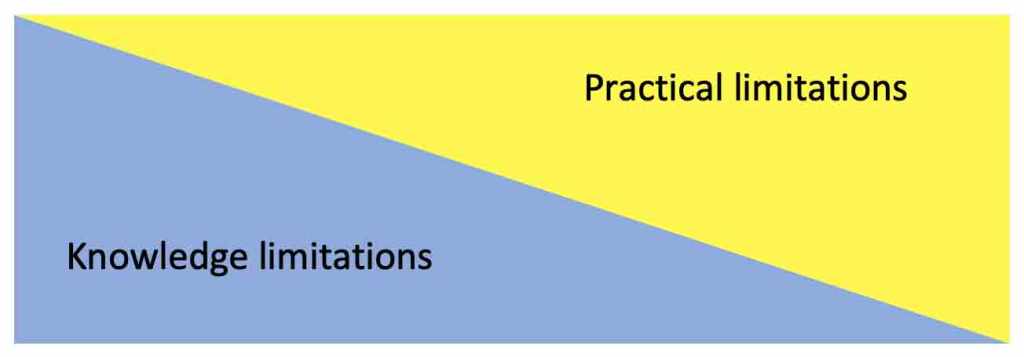

I’ve tried to encapsulate this as two overlapping triangles in the diagram below. The reason why we cannot name a specimen distils into one of two reasons: limitations of knowledge (represented by the blue triangle) or practical limitations such as the quality of the microscope or the way that the specimen presents on the microscope slide. So every identification challenge sits somewhere on the gradient from left to right: we are either limited by available knowledge or practicalities.

The challenges involved in identifying diatoms (and other microscopic organisms) fall into two types: the quality of the knowledge that we have available, and our ability to link this knowledge to the specimen we see under our microscope.

Knowledge limitations encapsulates everything that is known at the time that the specimen is being analysed, and will include the following:

- The species within a genus may have not yet been fully discriminated and described for the region you are studying;

- There are limitations associated with light microscopy which means that the full range of genetic variation within a complex of species cannot be resolved (“crypticity”).

- The literature for that genus is dispersed in numerous journal articles rather than gathered in a single accessible volume. In theory, we can access these via Google Scholar or Web of Science, but some will be behind paywalls. Sometimes, knowing where to look is, itself, the problem.

- The keys in taxonomic works are often poor (which inhibits identification by logical reasoning) and/or there may be insufficient images (inhibiting pattern recognition) and there is often insufficient focus on critical differentiating characteristics.

Next, there are problems that relate to the practicalities of identification, irrespective of the knowledge that is available:

- Individual cells do not present in an optimal manner (e.g. as girdle views in the case of diatoms) or key diagnostic criteria are absent (reproductive organs are necessary to identify species of filamentous algae such as Spirogyra and Oedogonium) or the taxon is sufficiently sparse in the sample that the full range of morphological and diagnostic characteristics cannot be discerned.

- Equipment available is not sufficiently sensitive. A common problem when instructing students is that microscopes used in university teaching laboratories have a lower specification than those used for research, so the students often cannot see the same level of detail that the textbooks assume. A twist on this general theme is that the camera on a microscope used for routine analyses cannot capture the level of detail required to allow someone else to identify a specimen when you email them an image.

- The observer is unaware of recent literature or is working under time constraints that prevent a full literature search. This is similar to the third point in the “knowledge” section, reflecting a second facet: problems arise not only because specialists are no longer prepared to write detailed monographs that gather together the literature on a genus in a region, but also because time and budget limitations mean that the alternative – thorough interrogation of a very diffuse literature – is not always possible.

- Faulty memory links a particular set of morphological properties to the wrong name. Mistakes, in other words. There is a danger that our recollection of the properties associated with a particular name drifts over time, and needs regular calibration.

In reality, I often have to make a judgement about the value of any extra information that I can glean from a sample, relative to the effort I will need to in order to unlock this information. There is a basic scientific curiosity in me that wants to know the identity of an alga I’ve never seen before, and to understand the diversity within a habitat better, but I’m also often working under pressure and spending time trying to name a single cell whose identity eludes me will add very little to the interpretation based on the other 299 cells I’ve already examined and named. On the other hand, if there was a single volume work on the Fragilaria of Europe (for example), the marginal effort required to make that extra determination might be reduced so that I can pluck the book from my shelf, flick through the pages, name it and move on. The danger of this lies in the first point I made – about incompleteness in our basic understanding of the variety within most genera – and means that a monograph may, itself, not be sufficiently comprehensive. “Hard cases” will be force fitted to available descriptions, perpetuating the longer term problem of fitting morphology-based descriptions to the biological species concept.

There was a time, not so long ago, when there was a general belief that there was a finite number of cosmopolitan species of freshwater diatoms, and an unspoken assumption that all could be differentiated with light microscopy. Over the last thirty years, those ideas have been superseded as forms once regarded as a single species have been fragmented into a multitude of distinct entities. No-one seriously doubts that there are many more species than diatomists a generation older than us had contemplated, but one side-effect is that the capacity of Linnaean taxonomy to serve as helpful “tags” that ensure consistency in identification between scientists is close to breaking-point. The craft of identification depends to a large extent on the willingness of taxonomists to invest time not just in expanding our knowledge but also in gathering this together into practical resources. That’s now become such a Sisyphean task that few seem to want to take it on. Yet, not having such resource creates problems of its own, not least in contributing to a sense amongst bureaucrats that diatomists are better at talking the talk than walking the walk, in terms of their ability to contribute to answering the pressing environmental challenges of our day.

Some other highlights from this week:

Wrote this whilst listening to: New Energy by Four Tet.

Currently reading: Still on Amy-Jane Beer’s Flow. Her explorations of British rivers includes a snorkalling trip in West Beck / River Hull which I wrote about in “Past Glories …”.

Cultural highlight: A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography – an exhibition at the Tate Modern in London.

Culinary highlight: When I first started this post, I was in Belgrade, eating traditional Serbian food in the Tri Seseria restaurant in Belgrade’s old town. That was in an unseasonably warm October, and the unfinished post has sat on my laptop for almost three months awaiting completion.