One of my favourite walks in the northern Pennines is along the Nent valley from Foreshield to Alston, the highest market town in England, and back. It is just a few miles long and the walk is far from strenuous, but it is a beautiful little valley and to be able to walk in shirtsleeves in late September is an unexpected bonus.

The irony is that the River Nent is one of the most polluted rivers in the region, bearing the drainage from numerous mines and spoil heaps on the surrounding hillsides. I’ve written about the effect of the toxic mine effluents on the River Nent elsewhere (see ‘East of Eden’ in Of Microscopes and Monsters) but today my attention has been grabbed by an alga that I did not mention in that account. I am standing at the point where the river flows over a limestone pavement, at Gossipgate, a kilometre or so above Alston itself, and looking down at a rock hollow that has a bright lipstick-red crust.

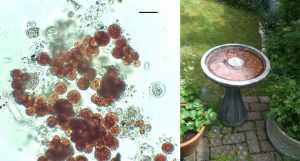

The River Nent flowing past limestone pavement at Gossipgate, just above Alston, Cumbria and (right) a hollow on the limestone pavement with a crust of Haematococcus pluvialis.

Under the microscope, this crust reveals itself as a series of spherical cells, almost entirely filled with red pigment. The name of this alga is Haematococcus pluvialis, and it is characteristic of situations which dry out frequently. It is not just found in rock hollows, such as the ones I saw beside the River Nent; another favourite haunt is in bird baths. Surprisingly, given its colour, this alga is more closely related to green algae such as Bulbochaete than it is to the group we commonly call “red algae”. Conversely, if you think back to posts on Audouinella and Lemanea, you will recall that red algae are not necessarily red. The red colour in Haematococcus is a compound called astaxanthin. The red cells that I saw at the River Nent are actually cysts which allow the cell to survive periods out of the water. Because the cells are exposed to the full glare of the sun, they produce astaxanthin as a natural sunscreen.

Left: Resting cells of Haematococcus pluvialis from the River Nent. Scale bar: 20 micrometres (1/50th of a millimetre); right: Haematococcus in a bird bath in London.

You may be surprised to know that you have probably eaten astaxanthin within the past month, and almost certainly consumed many related compounds. The intense red colour of astaxanthin means that it is a popular food additive and Haematococcus is grown commercially for this purpose. Astaxanthin is the reason why the flesh of farmed salmon is often redder in colour than the flesh of wild salmon, but it is added to many other foods as well during the production phase. If you saw “algae” on a menu, you might well turn up your nose and order something different. However, algae creep into your diet in all sorts of unexpected ways without you ever knowing.

Pingback: At last … a red alga that really is red … | microscopesandmonsters

Pingback: Fake tans in the Yorkshire Dales | microscopesandmonsters

Thank you for this – we were walking the Nent today and this article has answered all the questions we had regarding the red and green. A fine piece of writing and research.

Pingback: Good vibrations under the Suffolk sun … – microscopesandmonsters

Pingback: Little round green things … – microscopesandmonsters

Pingback: Secular icons? – microscopesandmonsters

Pingback: Algae in a stone forest – microscopesandmonsters