Despite my predictions in “Lower forms of pondlife …”, our garden pond is greener now than it was back in April when I last wrote about it. The frog spawn has hatched into tadpoles but these do not seem to have had the impact that I expected. If anything, based on a quick visual assessment, the zooplankton which we did see swimming in the open areas are less numerous than earlier in the year. Maybe the tadpoles are selectively eating these, which might result in less grazing and, as a result, more algae. However, the green algae in the pond are mostly very small flagellated cells which are extremely hard to photograph, let alone identify.

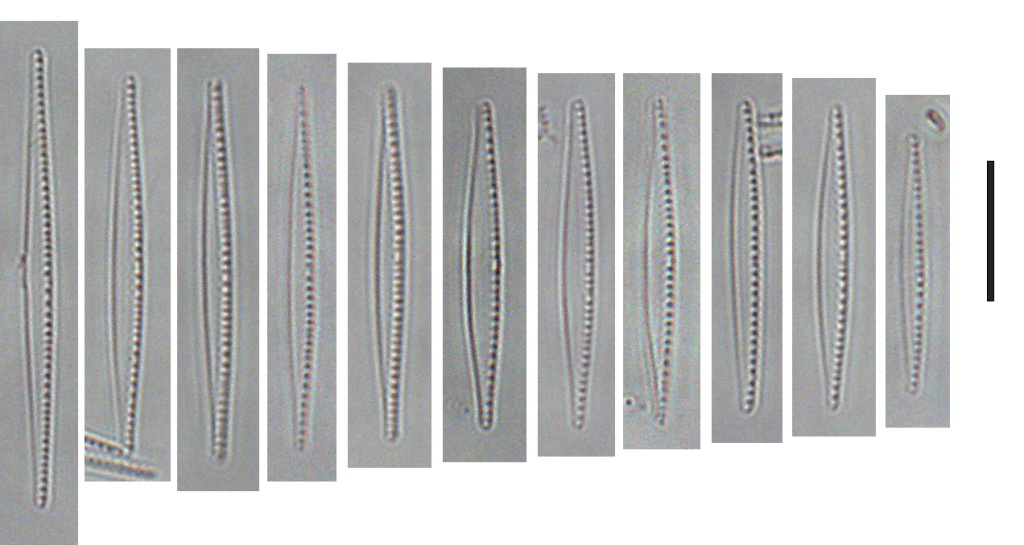

Alongside these investigations of the state of the pond in May, I’ve also been looking in more detail at the diatoms I found back in April. The most abundant diatom turned out to be Nitzschia paleacea. I had initially thought that this was Fragilaria gracilis, but although the outline and habit were very similar, the chloroplast arrangement, which would have been indicative of Nitzschia rather than Fragilaria, was not easy to see. The other giveaway that would have led me to Nitzschia rather than Fragilaria is the presence of “fibulae” – silica struts that support the raphe canal. However, the fibulae on N. paleacea are very fine and, again, quite hard to see on live material. Some books claim that N. paleacea can also be found in the plankton, with the cells joined at the base to form radial colonies. However, I did not see any freely-suspended in the samples that I looked at. They were clustered on the Oedogonium filaments, again, in a very Fragilaria-like manner and, due to their very fine structure the characteristic two chloroplast arrangement was difficult to see.

Nitzschia paleacea from our garden pond, April 2023. Scale bar: 10 micrometres (= 1/100th of a millimetre). The picture at the top shows the pond a month later with water crowfoot in flower.

I normally encounter Nitzschia as single cells moving through biofilms, constantly adjusting their position to maximise their access to light and other resources. Fragilaria, the genus which I had initially mistaken them for, lacks a raphe (the organelle responsible for movement) but do have an “apical pore plate” at one pole through which mucilage is extruded to enable them to attach. There is little in the literature, as far as I can see, on how Nitzschia can switch between motile and attached forms. However, there are reports of planktonic forms where cells aggregate to form stellate colonies. That, too, implies attachment via the base. This is a relatively uncommon habit for the genus – only four of 77 species listed in Freshwater Benthic Diatoms of Central Europe have references to the possibility of a planktonic lifestyle, two of which (N. fructicosa, N paleacea) are noted to form stellate colonies. Interestingly, the N. paleacea I observed growing on our pond’s Oedogonium were all attached separately rather than occurring in clusters whereas I often see epiphytic Fragilaria spp in clusters.

We need to remember, however, that the strong bias of diatom studies towards benthic habitats and with a focus on cleaned valves means that many of the nuances of the ecology of individual species are missing. My guess is that expression of these traits is an opportunistic response to local conditions rather than being hardwired into their genome. It may be that some species are more likely to express these than others, but it is also possible that a few recorded instances have, by dint of being written into a book and, because of the ways in which modern diatomists work, is rarely contradicted by new observations and so becomes dogma.

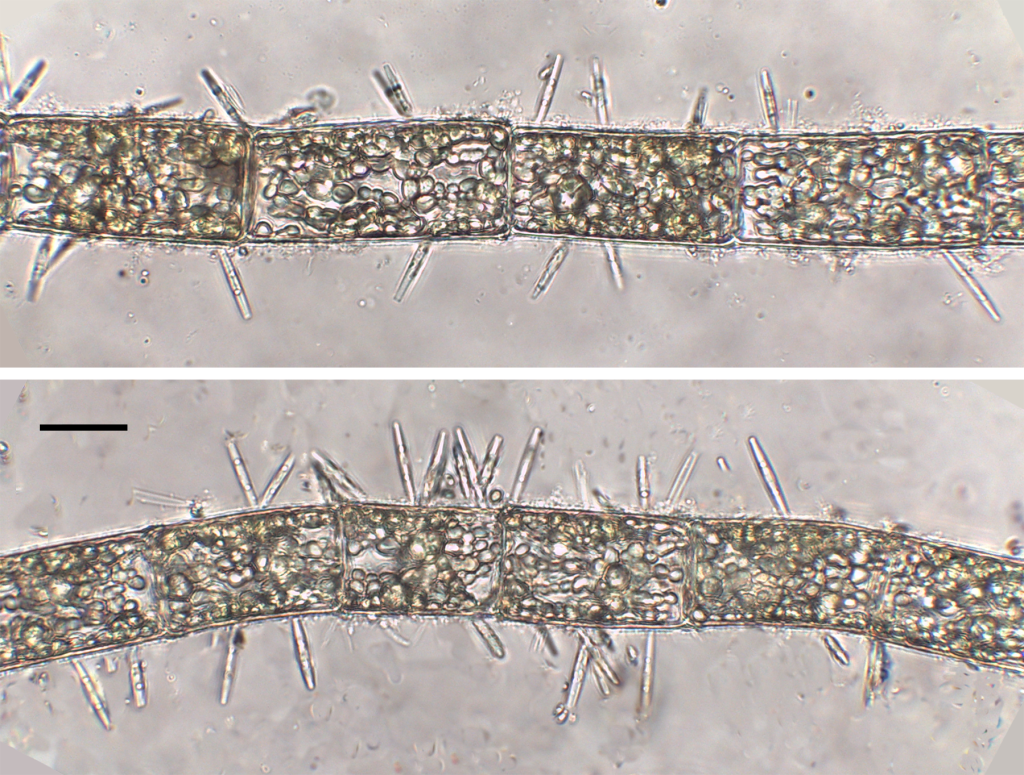

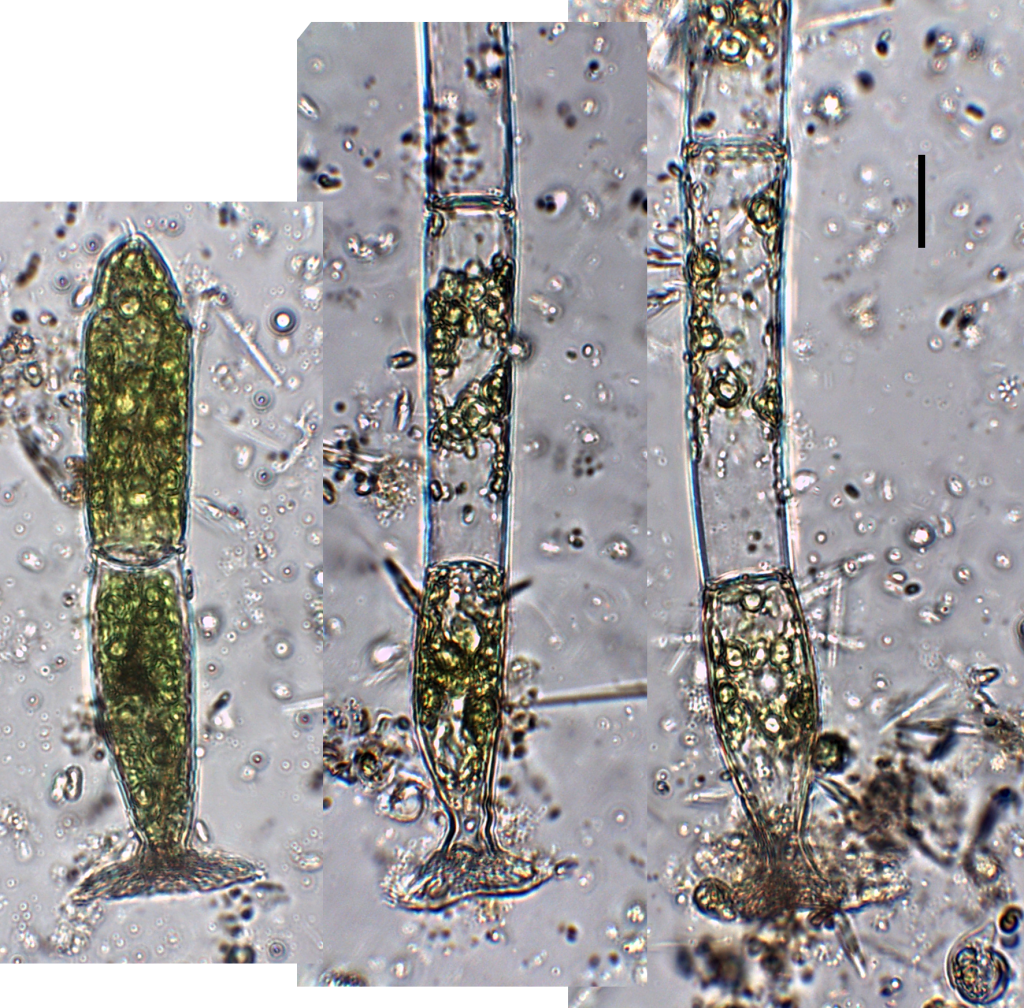

Oedogonium filaments with epiphytic Nitzschia paleacea from our garden pond, June 2023. Scale bar: 20 micrometres (= 1/50th of a millimetre).

The title of this post, incidentally, carries on my predilection for music-based puns. “Different Class” is, of course, a classic album by Pulp, featuring their most famous song, Common People. “Class” is also a term that has a taxonomic meaning which meant that the title should work as a way of drawing attention to the identification errors that had dogged my investigation. However, the arrangement of higher taxonomic groups of diatoms is, itself, still evolving (see “Who do you think you are?”) and the latest system (as used on www.algaebase.com) places both Nitzschia and Fragilaria in the same class, Bacillariophyceae but different subclasses (Bacillariophycidae and Fragilariophycidae respectively). “Different Subclass” just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

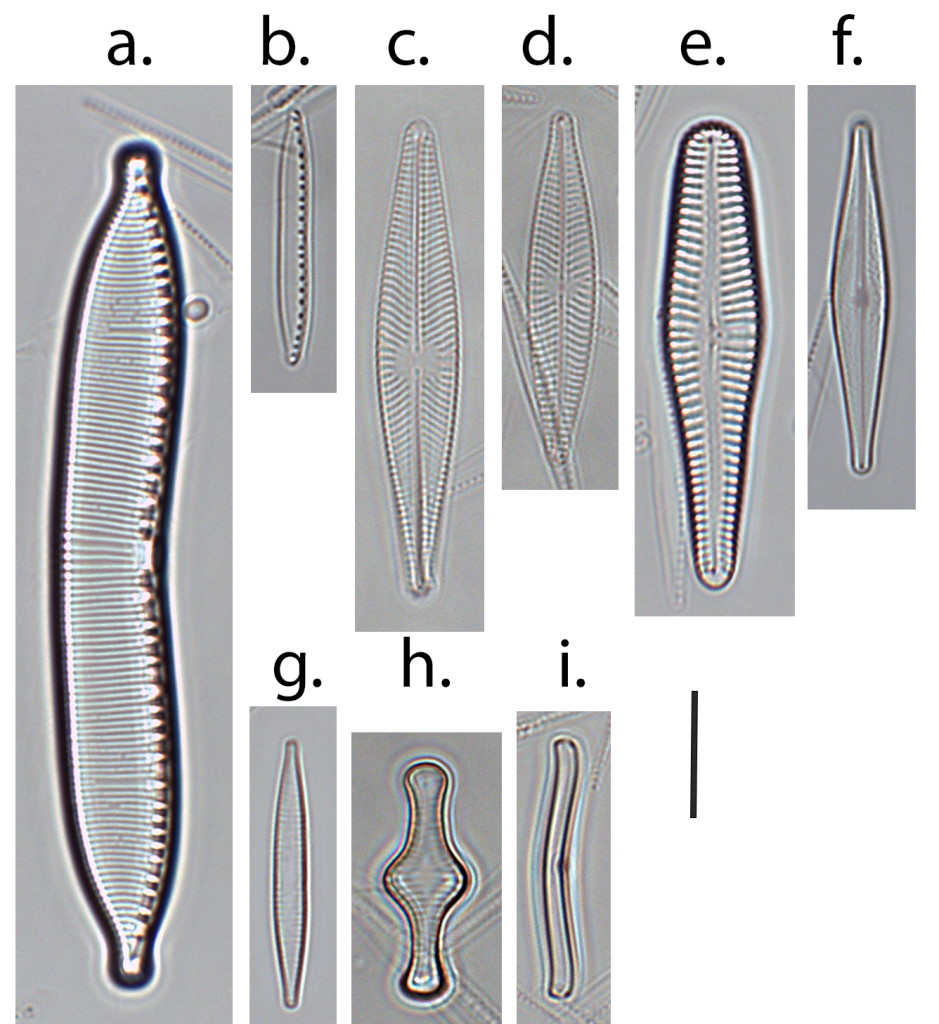

Some other diatoms from our garden pond: a. Hantzschia amphioxys; b. Nitzschia frustulum; c., d. Navicula cryptocephala; e. Gomphonema subclavatum; f. Brachysira microcephala; g. Fragilaria gracilis; h. Tabellaria flocculosa; i. Achnanthidium sp. (girdle view). Scale bar: 10 micrometres (= 1/100th of a millimetre). All were present in trace amounts relative to Nitzschia paleacea.

Some other highlights from this week:

Wrote this whilst listening to: Classic late 60s/early 70s blues band, Groundhogs, following the recent death of their guitarist Tony McPhee. Also É Soul Cultura volume 2: complilation album by Manchester DJ Luke Una.

Currently reading: Chasing the Monsoon by Alexander Frater, old-school travelogue about India. Also Small Things Like These, excellent Booker Prize-nominated novella by Claire Keegan

Cultural highlight: Reality, excellent US film about a whistleblower working in US Intelligence. Script is taken verbatim from the FBI recording of her interrogation. The protagonist, incidentally, received a five year prison sentence for exactly the same crime for which Trump has just been charged.

Culinary highlight: pork gyros in Newcastle straight after our cinema trip. Took me straight back to Cyprus …