Our visit to Rila Monastery was one of the cultural highlights of our trip to Bulgaria in the summer (see “The art of icons …”) with the added bonus that it is set amidst some spectacular scenery. The monastery was founded by St Ivan Rilski (“St John of Rila”) in the 10th century, though the present structures date from the 19th century. St Ivan, I gleaned from my reading, shared a love of nature with St Francis and St Cuthbert and Rila’s remote location reflects his desire to live the life of a hermit.

Beyond the monastery the road twists and turns amidst the forest that lines the valley. Occasionally, the canopy is broken by meadows and orchards of apricot and plum trees. The apricots were ripe for harvest and at an easy height for foraging as we passed by. We were too late in the year to find many wild flowers in these meadows but the absence of any of the paraphernalia associated with intensive agriculture made us suspect that these would have been a riot of colour in the spring. Eventually, we came to a small hamlet set amidst a wider area of meadows, where we refuelled at a small café serving the delicious local bean soup (“bob chorba”) before making our way across the meadow to the stream.

A haystack in a meadow near Rila Monestery, August 2017.

The Rila stream itself flowed through a densely-wooded channel, with a variety of substrates from coarse sand to moss-covered boulders. The larger stones were mostly granite, reflecting the underlying geology of the region, which almost certainly means that the water was very soft. The surrounding vegetation and low population density also mean that the water is probably as pure as we are likely to find anywhere in Europe. I had a toothbrush and sample bottle in the bottom of my rucksack and scrubbed a few cobble-sized stones to remove the thin surface film and stowed this for the journey back down the valley.

Sampling Rila stream at Kirilova meadows, a few kilometres upstream from Rila Monestery in August 2017. The photograph at the top of the post shows the scenery around Kirilova meadows.

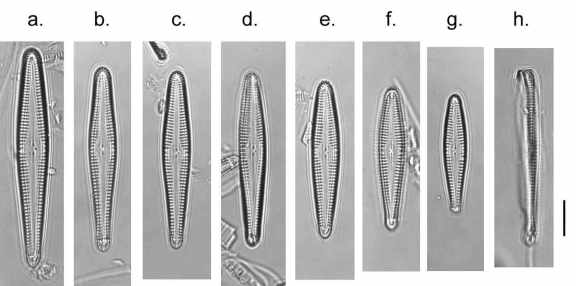

It has taken until now for me to get around to looking at this sample, which turned out to have a large population of Gomphonema rhombicum, along with quite a lot of Achnanthidium minutissimum and relatives, confirming my suspicion of a circumneutral, low nutrient environment. G. rhombicium is a relatively uncommon diatom, so I was intrigued to have a closer look. It has a similar outline to G. pumilum, which is very common, but is larger and has a distinct broad lanceolate axial area and, consequently, relatively short striae. The axial area broadens out a little further at the central area, where there is also a single stigmoid. I wish now that I had had a look at the sample before digestion as many of the larger Gomphonema species have long mucilaginous stalks, whereas G. pumilum and relatives tend to be attached to the substrate by short mucilaginous pads. I can find nothing in the literature that alludes to the habit of the living cell and, on this particular occasion, am in no position to judge the shortcomings of my peers.

By coincidence, the type location for Gomphonema rhombicum is given as “Appleby, Westmoreland”, which is just over an hour’s drive from where I live. The most obvious place to hunt for G. rhombicum would be the River Eden; however, the scant details on the ecology of G. rhombicum that I can find suggest a preference for softer water than found here. This is a geologically-complex area so there is a possibility of suitable habitat existing in a stream in the vicinity. If the Eden was the location from which the original population of G. rhombicum was collected, then I suspect that it may have been a casualty of the agricultural intensification that has taken place in this area since it was first described.

Cleaned valves of Gomphonema rhombicum from Rila stream at Kirilova meadows, August 2017. a. – g. show valve views; h. shows a girdle view. The scale bar is 10 micrometres (= 100th of a millimetre).

That leaves me with just one option: a return to the Rila National Park. I think I can just about live with that. We stayed at Hotel Pchelina, a few kilometres down the valley from Rila Monestery and our dinner that evening was the most delicious grilled trout that I have ever tasted. If a return visit was needed to solve the mystery of Gomphonema rhombicum’s habit then I think that is a hardship with which I can just about cope …

Reference

Iserentant, R. & Ector, L. (1996). Gomphonema rhombicum M. Schmidt (Bacillariophyta): typification et description en microscopie optique. Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture 341/342: 115-124.

You are living the life. ❤