My final post of 2023 (“Call me by my name …”) looked at the fraught business of putting names onto microscopic organisms, dividing the problem into limitations of knowledge and practical challenges. Limitations of knowledge mean that there is no single definitive work to which we can refer. Practical challenges include limitations of our equipment but also our capacity to access an increasingly diffuse literature, some of which sits behind internet paywalls. At the intersection of these two challenges sit “cryptic species”: those that we know exist, but which cannot reasonably be differentiated with light microscopy.

In many parts of the world, diatoms are used as part of statutory assessments of freshwater health so it is worth asking ourselves just how much extra sensitivity we may unlock by accessing all this unknown and hidden information about diatom species. How might we do that? The dominant approach to naming diatoms uses characteristic shapes and structures to differentiate species so we need to find a way of differentiating all the variety within diatoms that does not rely upon our ability to see and describe this variation. The answer lies in molecular genetics where, rather than using morphology, we differentiate using sequences of DNA. Until now, though, people have mostly tried to link these sequences to traditional names defined by (you’ve guessed it …) our inherently-flawed system of shape- and character-based taxonomy. Suppose that, instead of this, we did all steps required of DNA-based identification except for that final one where we fitted the outputs to traditional names. How would that change the situation?

About 2800 diatoms have been recorded from the UK and Ireland, based on traditional shape-based species concepts. Our study, based on a dataset of 1220 samples from rivers all around the UK, we found 4036 distinct entities. Not all of these will be “species” in the traditional sense but, on the other hand, some of the sequences we identified may encompass more than one species. Metabarcoding uses relatively short fragments of DNA from a single gene whereas taxonomists would work with longer lengths of two or more genes as well as morphology. However, this does at least offer us a ballpark figure for how many diatom species we are yet to find. Very roughly, for every two diatom species we already know about, there is one more waiting to be described. As our dataset comes from rivers, we are probably missing some of the diversity in lakes and soil, so the true figure may be even higher.

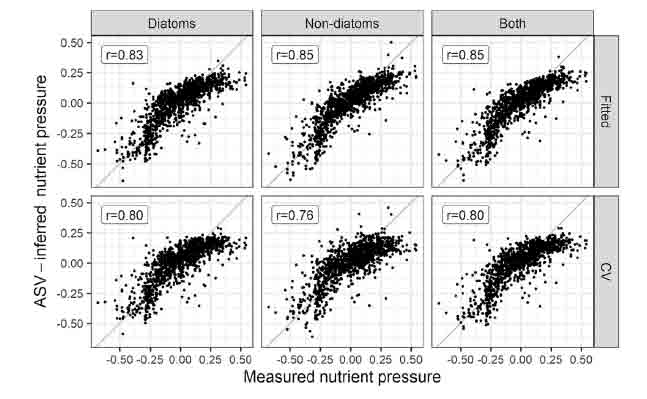

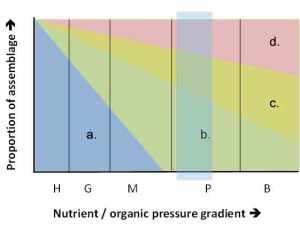

Our primary purpose in doing these analyses was to see if we could improve the models we use for statutory assessments. Way back in 1995 when I put together the first version of the Trophic Diatom Index (TDI), it explained 63 percent of the variation in the river phosphorus gradient. Since then, the TDI has gone through several iterations as species have been added and coefficients have been tweaked but, until this study, we always used traditional diatom species names (even when using molecular genetics to generate our data). Now, almost 30 years since the first version of the TDI, we generated a model that bypassed traditional names (and all the limitations this introduces) and produced a model which explained 72 percent of the variation in the nutrient gradient.

Results of weighted-average (WA) predictive models, showing relationship between observed and ASV-inferred nutrient pressure for diatoms and non-diatoms, and both (combined) (left). Upper plots show relationship for model fits, lower plots show results after 2-fold leave-out cross validation. See Kelly et al. (2024) for more details. The figure at the top is the graphical abstract from this paper.

This is not a perfect statistical comparison, but it reflects the reality of the situation. We captured most of the diatom v nutrient signal with our relatively crude approach back in the early 1990s and have spent the last 30 years crawling slowly towards the asymptote. We calculated that the strongest model we could compute with the (imperfect) chemical data we are given is, in theory, 86 per cent. However, that assumes no other factors are influencing the diatoms and we know that is not the case. Whilst strong models should allow regulators to better predict the ecological benefits of reducing phosphorus, there is also a danger that we become blind to the complexity of river systems in the process of developing these.

Our result suggests that, however hard taxonomists work to track down the 1200 or so “missing” species, this will add relatively little functionality to our current mode of assessment. Of course, having a better idea of the diversity of the algae of Britain and Ireland is a worthwhile end in its own right, although some of this diversity will be “cryptic”, impossible to unlock with conventional microscopy. The answer is to find new ways to use this rich source of information rather than refining existing approaches.

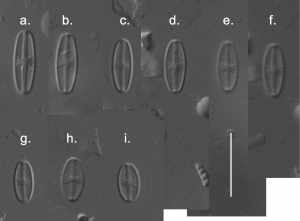

The problem, as we attempt to unravel this diversity and explain it in terms that can be used when identifying diatoms using a microscope is that we are encountering many of these 1200 “missing” species all the time. They are hiding in plain sight, but we are not recognising them as discrete species because no-one has told us how to differentiate them from their near-neighbours. The challenge for taxonomists is to capture the characteristics of these unambiguously using words and pictures, when many of the characters visible with the light microscope will overlap with those of near neighbours. Otherwise, the sensitivity gained by extra knowledge will be cancelled out by error introduced by mis-identifications resulting from ambiguous and diffuse literature. We are almost back where we started, still channelling the spirit of van Leuwenhoek four hundred years ago, struggling to make sense of realms that sit at the borders of our awareness …

References

Kelly, M. G., & Whitton, B. A. (1995). The trophic diatom index: a new index for monitoring eutrophication in rivers. Journal of applied phycology 7: 433-444.

Kelly, M. G., Mann, D. G., Taylor, J. D., Juggins, S., Walsh, K., Pitt, J. A., & Read, D. (2023). Maximising environmental pressure-response relationship signals from diatom-based metabarcoding in rivers. Science of The Total Environment 914: 169445.

Some other highlights from this week:

Wrote this whilst listening to: music referred to in Do Not Say We Have Nothing (see below). In particular, Pink Floyd’s Set the Controls to the Heart of the Sun and Mahler’s Das Liede von der Erde, both of which have words derived from ancient Chinese poetry.

Currently reading: Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien, a novel that spans Chinese history from the Sino-Japanese war to Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Cultural highlight: Mercury-prize nominated Irish band Lankum at the Boiler Shop in Newcastle. Traditional folk instrumentation but with enough of a nod to My Bloody Valentine to make me want to gaze at my shoes at times.

Culinary highlight: fillets of sea bass roasted and served over a bed of pan-fried fennel. A recipe from a book of Venetian recipes that we had forgotten we had.