I have not been to my regular haunts in the western Lake District for two months now. We usual collect samples at two month intervals but our August trip was compromised by the wet weather we had during the latter part of the summer. You can see the evidence for this in the graph below, showing how river levels fluctuated. I should point out that, for personal safety reasons, we can only go out when the river is low so even the values during the latter part of August would have made wading problematic. Samplers, it was once pointed out to me, are part of the benthos, not part of the plankton. Also, values on the river level graph are recorded at the gauging station, and will not be the same at the point where we sample. We have learned, over the years, to make a mental adjustment to get a sense of what conditions will be like when we arrive.

By early September, however, levels were low once again but, annoyingly, I had other commitments, including the course I wrote about in “Cyanobacteria inside their comfort zones …”. Anticipating river conditions based on weather forecasts and juggling with other diary commitments is all part of the job. This particular trip has been harder to organise than most. I have had to make and cancel hotel reservations on three separate occasions, and on a fourth, I drove across and stayed overnight, only to find the rivers were higher than I had hoped when I checked the hydrograph first thing in the morning.

River levels in the River Cocker (Scale Hill) from 1 August to the time of writing. Data from www.riverlevels.uk. Values are averages for each day and the dashed line is the level on the day of my visit. The photograph at the top of the post shows Oedogonium growing on submerged stones in the River Cocker at Low Lorton.

When I finally got to the River Cocker, I was greeted by the sight of lush growths of green algae across the riverbed. This turned out to be a near-monoculture of Oedogonium, which we last encountered in the River Derwent earlier in the summer (see “Borrowdale landscapes …”). It is a very common genus, albeit one that is very hard to identify to species and also one for which generalisations about ecology are difficult.

What I can say, with some confidence, is that the quantity of algae present in these streams waxes and wanes in a predictable manner, with highest values recorded in winter, but it is not so easy to say which species will proliferate on any particular occasion. That also gives us a clue about the possible reason for the patterns that we see: because the biomass fluxes happens at a number of sites across several catchments, irrespective of which species are present, it must be driven by external factors that are common to all of these sites. And because the fluxes are most extreme in rivers that are downstream of lakes (as is the case for the Cocker), we suspect that temperature plays a role. Because water has a high specific heat capacity, Crummock Water acts as a huge “heat pump”, making the water in the Cocker ever so slightly warmer during autumn and early winter than is the case in nearby rivers that do not drain out of lakes.

Filamentous algae are well placed to take advantage of this growth as they are simple and straightforward photosynthesis machines. Sunlight is trapped by their chloroplasts and converted into the building blocks of cells which divide mitotically, allowing biomass to accrue without the complications faced by more sophisticated organisms. There is a certain amount of phenological control in some filamentous algae, but this is mostly concerned with the onset of sexual reproduction (see “The intricate ecology of green slime …”). Most of the time, filamentous algae don’t see the need for sexual reproduction (see “Tales from the splash zone …”) so the Oedogonium in the River Cocker is free to take advantage of the slightly warmer water compared to nearby streams, and convert as much of the late autumn sunlight as possible. Meanwhile, the bugs that normally graze away any algae that cover submerged stones are dancing to the tunes played by their own internal clocks and lack the capacity to increase as quickly as their food supply. The result is the green riverbed that I saw in the River Cocker when I visited.

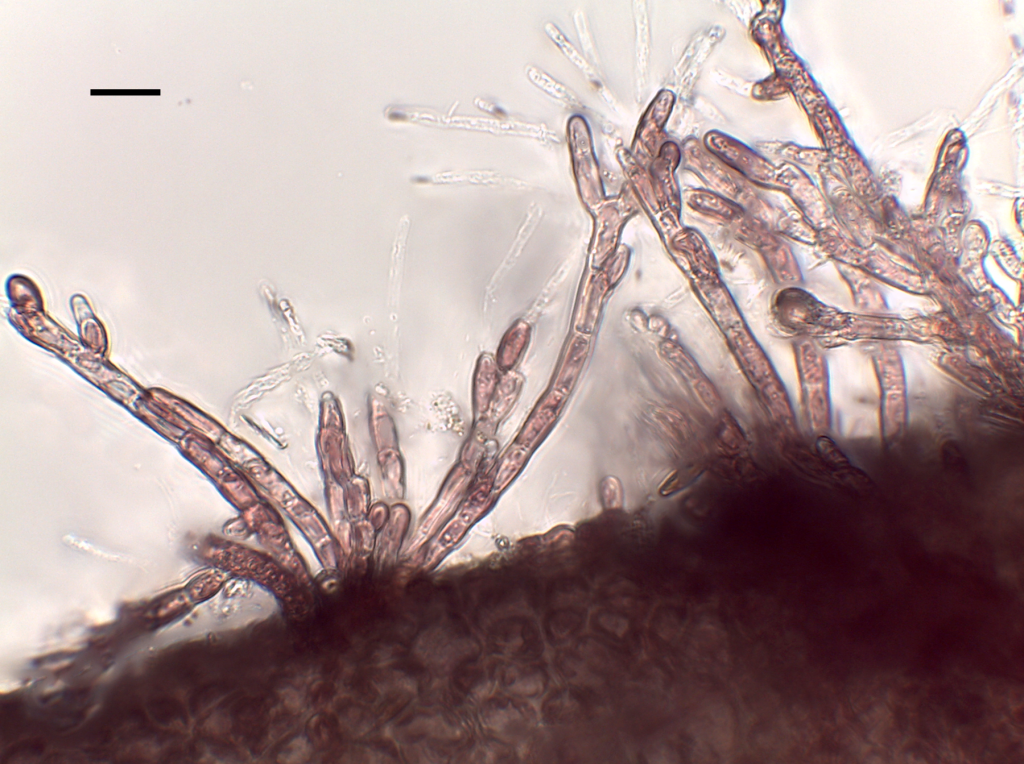

Oedogonium filaments from the River Cocker, October 2023. The lower image shows a cell with a number of cap cells. Scale bar: 20 micrometres (= 1/50th of a millimetre).

My comment about Oedogonium being able to accrue biomass without the complications faced by larger organisms needs a little qualification, because not every cell is able to divide. The photograph above shows a cell with a fine collection of “caps”, demonstrating that it has divided numerous times. There is, in other words, a first tentative step towards specialisation of cell function and, from this, we may also infer some redistribution of photosynthesis products along the filaments.

Some of these “cap cells” were conspicuously brown compared to the cells on either side. This is quite a common sight but I have found nothing in the literature that may explain what is going on. The colour is suggestive of ochre and my working hypothesis is that these cap cells are particularly metabolically active, requiring the chloroplasts in the cell to work harder than the cells on either side. This will mean that these cells evolve more oxygen and this, in turn, will mean that iron and manganese in the water are more likely to precipitate out. The lower photograph shows one of these brown cap cells colonised by diatoms (Gomphonema) and filamentous bacteria. Oedogonium often has a substantial payload of epiphytes but not usually concentrated in a few locations. Once again, what is it about the cap cells in particular that makes this a good location for other algae? The literature is silent.

More Oedogonium filaments from the River Cocker, October 2023, this time showing iron/manganese preciptitation around cap cells and associated epiphytes. Scale bar: 20 micrometres (= 1/50th of a millimetre).

I always leave my regular sampling locations curious about what I will see next time I visit. This time, however, this curiosity is leavened with a sense of trepidation as the long-term weather forecasts seem to suggest we are in for a wet autumn (driven by the El Niño in the western Pacific). As a result, I am also anticipating spending more time over the next few weeks poring over the hydrographs and weather forecasts trying to predict when river levels will be low enough to pull on my waders and get back into the river. Uncertainty will be the only certainty in my life over the next few weeks …

Some other highlights from this week:

Wrote this whilst listening to: Frankie Archer, who blends traditional folk music with electronica. I saw her on Later … with Jools Holland a couple of weeks ago and then found that she was playing at Darlington Library a few days later. Her haunting melodies have stayed with me …

Currently reading: Qian Zhonghsu’s Fortress Beseiged. Classic Chinese novel set on the eve of the Sino-Japanese war.

Cultural highlight: A Ken Loach double-bill: first, a stage adaptation of his film I, Daniel Blake at the Gala Durham, then his latest film The Old Oak at the Tyneside Cinema. The latter uses several locations in Co. Durham including Blackhall Rocks (see “County Durham’s tropical seashore”)

Culinary highlight: vegetarian tasting menu at Rebel in Heaton.