Much has changed in the two months since I was last at the River Irt. The conspicuous yellow-brown patches of diatoms that attracted my attention in Cold Comforts have gone, but other algae have appeared: clusters of dark brown filaments, each a couple of centimetres long, on the upper surface of boulders. These tufts are the red alga Lemanea fluviatilis, which I’ve written about before (see“Lemanea in the River Ehen”). Interestingly, I did not see Lemanea at Lund Bridge, the focus of the posts about winter diatoms, but at Cinderdale Bridge, a few kilometres further downstream. Lemanea is also not found in the River Ehen close to the outfall of Ennerdale Water but becomes abundant a few kilometres further downstream. There must be something about proximity to a lake that does not favour this genus.

Young shoots of Lemanea fluviatilis along with green algae on a boulder in the River Irt at Cinderdale Bridge, February 2023. The boulder is about 40 centimetres long. The photograph at the top of the post shows the River Irt at Cinderdale Bridge.

These filaments (which are actually hollow tubes of cells) had some growths which looked remarkably like another red alga common in streams hereabouts, Audouinella hermainii. But we could also turn that argument around and say that Audouinella looks remarkably like juvenile stages of several red algae (see “The complicated life of simple plants …”). Unravelling the identities of these simple filaments has kept taxonomists busy for over a century and molecular analyses are still presenting us with surprises. I’m going to assume that these are young gametophytes of Lemanea until someone convinces me otherwise, simply because of their proximity to so many other young shoots of Lemanea.

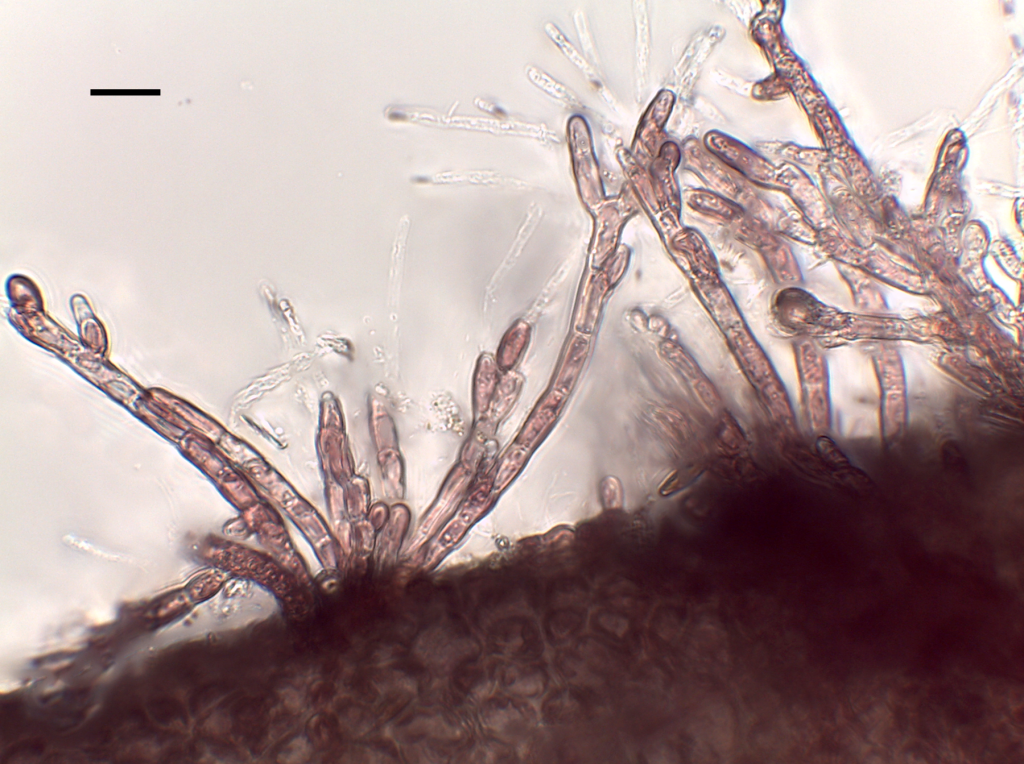

A filament of Lemanea fluviatilis with young epiphytic gametophytes. Scale bar: 100 micrometres (= 1/10th of a millimetre).

Close-up of young gametophytes on a filament of Lemanea fluviatilis in the River Irt, February 2023.

These were not the only residents on Lemanea. There were also some thin, unbranched filaments belonging to a cyanobacterial genus Chamaesiphon. This is a genus with two very distinct habits: some species form dark brown/black crusts on rocks (see “A bigger splash …”) whilst other species live as epiphytes. I last wrote about the epiphytic forms in “Whatever doesn’t kill you …”. In that post, I was circumspect about naming the species because I could only see a single “exospore” at the end of filaments. The population in the River Irt, however, has several filaments with a very characteristic stack of exospores so I can use the name C. confervicola with more confidence.

A young filament of Lemanea fluviatilis with epiphytic Chamaesiphon confervicola. A stack of exospores is visible on the filament to the left of centre. Scale bar: 20 micrometres (= 1/50th of a millimetre).

The last image in this post is a graph showing the changes in the cover of Lemanea fluviatilis in rivers in West Cumbria over the course of a year. This shows very clearly that Lemanea is most prolific in winter and spring, becoming very sparse in summer through to autumn. It is a similar pattern to that shown by Gomphonema. There are algae that have pronounced summer peaks but we tend not to see these in the very nutrient-poor streams of the Lake Disrict. My theory is that these small streams tend to be shaded and to have healthy populations of (hungry) invertebrates which are most active in the warm waters of summer. Consequently, winter offers the best opportunity for an alga to grow relatively unmolested. And, just as I showed how Gomphonema created a “housing estate” for other diatoms to inhabit, so Lemanea might well be determining the fluxes of the tiny Chamaesiphon confervicola filaments too.

Seasonal changes in the cover of Lemanea fluviatilis in rivers in West Cumbria, 2019 – 2023. Cover is expressed on the 9-point scale used for macrophyte surveys in the UK. Vertical lines separate the twelve months.

Some other highlights from this week:

Wrote this whilst listening to: In a Silent Way, by Miles Davies. My favourite of his many records.

Currently reading: Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: Our Year of Seasonal Eating by Barbara Kingsolver.

Cultural highlight: finally got around to seeing BAFTA-winning and Oscar nominated film Aftersun, starring Paul Mescal.

Culinary highlight: homemade prawn, crab and fennel cannelloni.