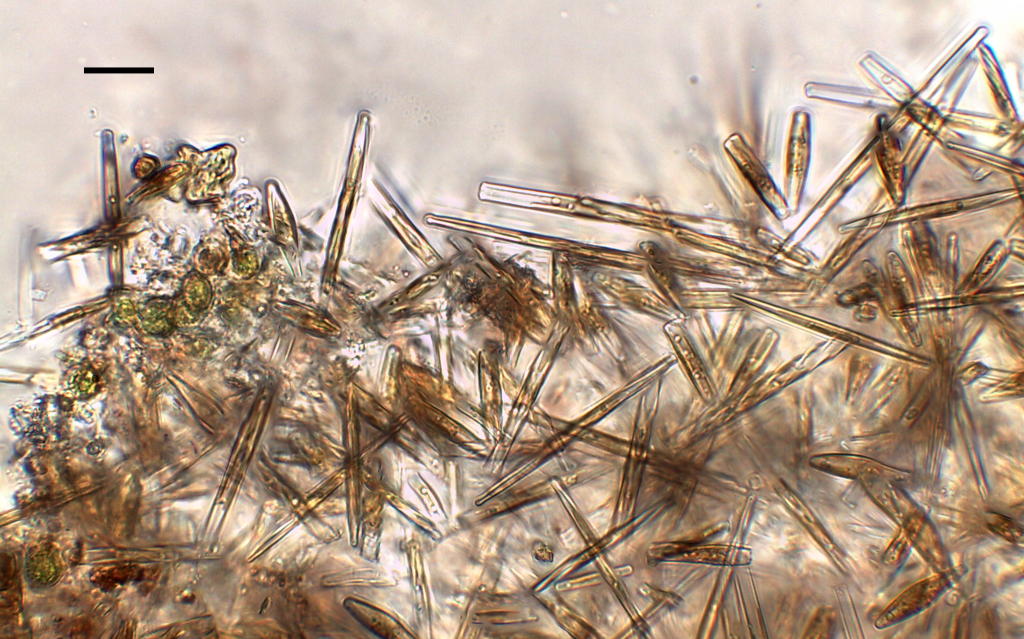

Having shown in two recent posts how the presence of one alga influences the quantity of many others in the River Irt, I thought I should see if this relationship holds in other streams in the region. As Gomphonema exilissimum was the “ecosystem engineer” in the River Irt, I started with Croasdale Beck because I knew that this, too, had abundant populations of Gomphonema at certain times of the year. Whereas the River Irt flows out of Wastwater, Croasdale Beck tumbles straight off the west Cumbrian fells. It is, as a result, a much flashier stream than the Irt, and this has a big effect on the stream’s algae.

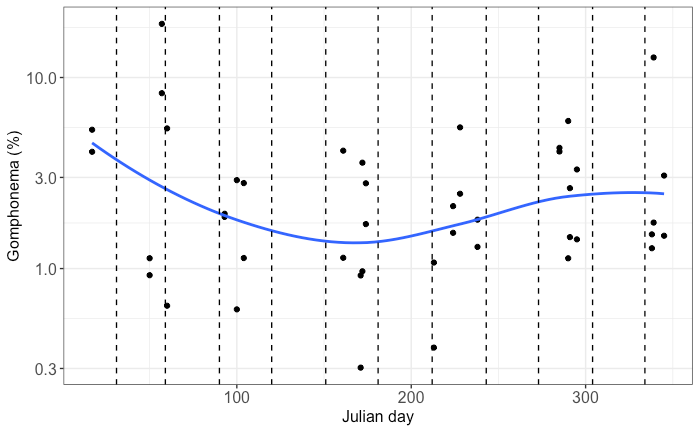

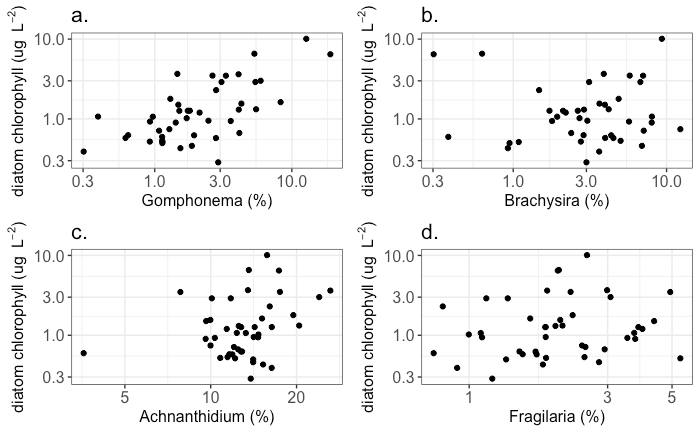

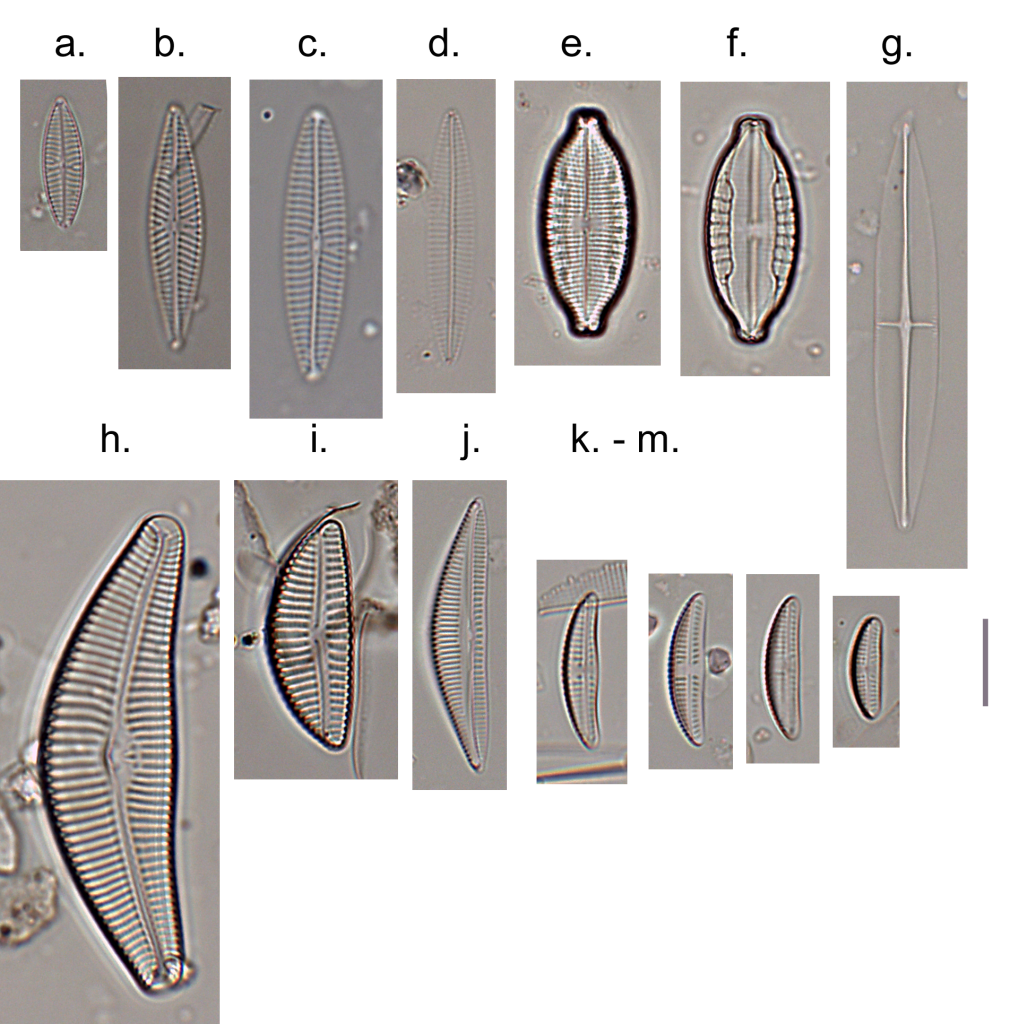

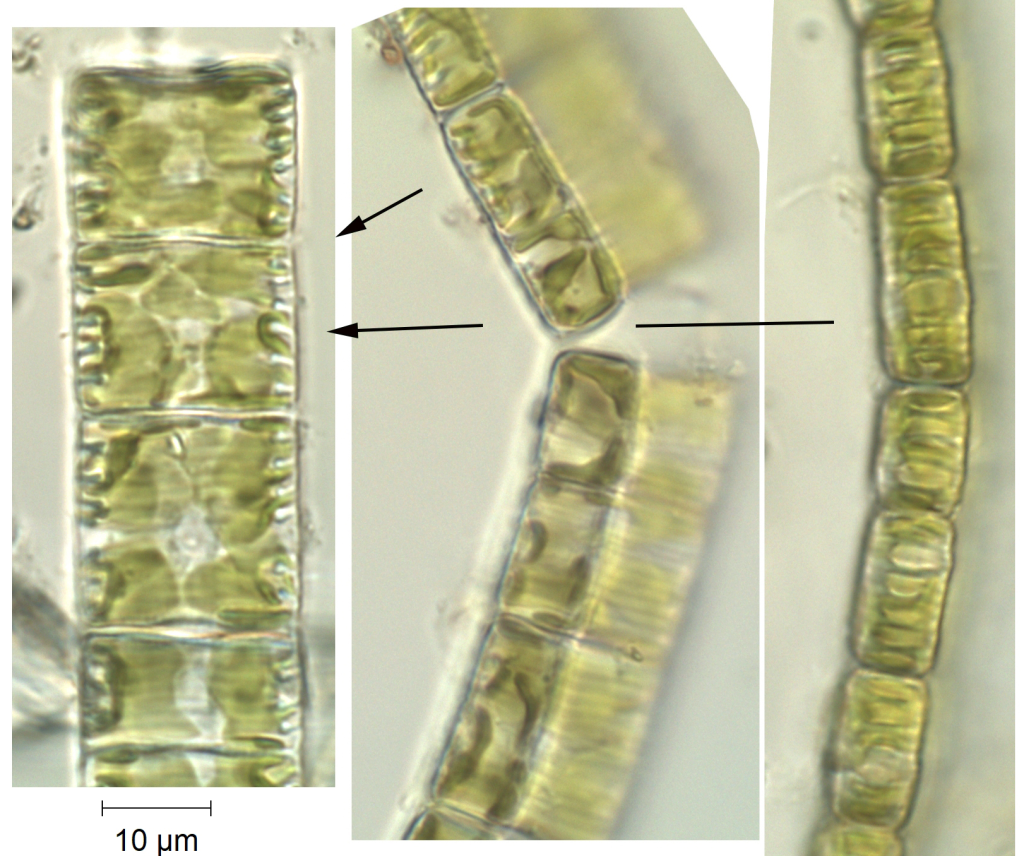

Gomphonema in Croasdale Beck shows the same general annual pattern as it does in the River Irt but without the coupling to diatom biomass that I showed in “High-rise habitats” (there are weak relationships, but these are not statistically-significant). The most abundant Gomphonema is different at the two sites I visit on Croasdale Beck: G. parvulum at the upper site and G. calcifugum at the lower one. Neither grows on long stalks in Croasdale Beck although I have certainly seen relatives of G. calcifugum form long stalks elsewhere in northern England (see: “And the Oscar for the best alga in a supporting role goes to …”). I suspect that the harsher conditions compared to the River Irt would mean that “high-rise” growth forms would get scoured away too frequently and that, in turn, means that there is less opportunity for other algae to exploit the habitat that a cushion of stalk-forming Gomphonema creates.

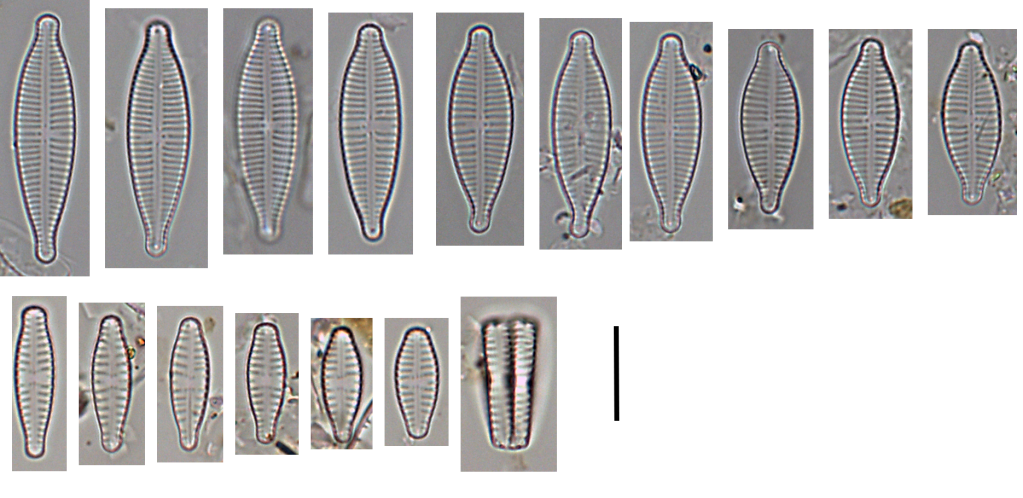

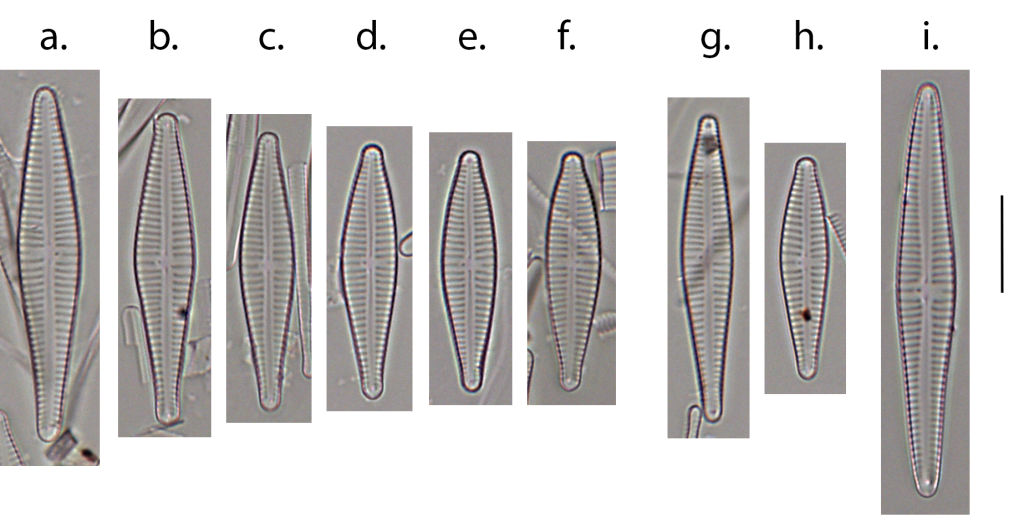

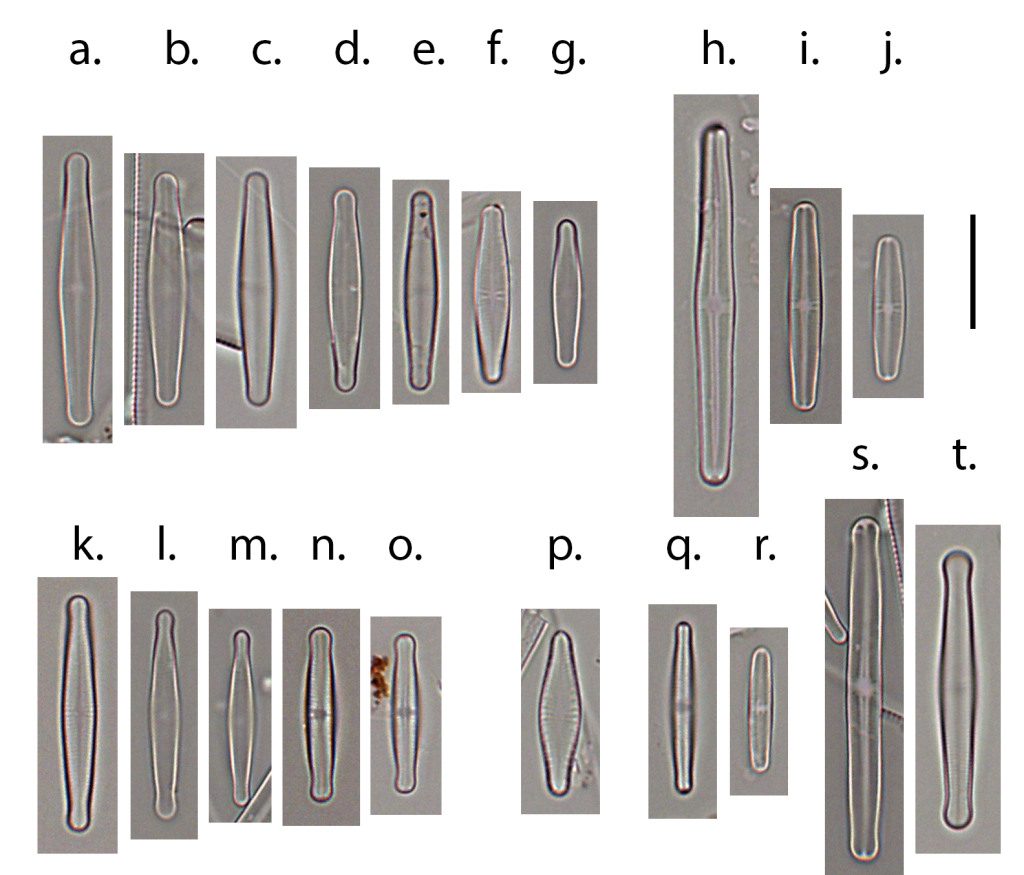

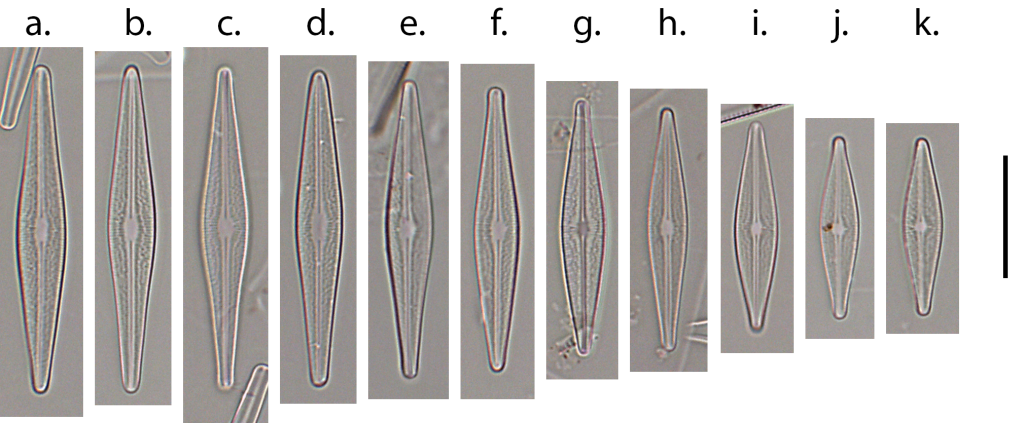

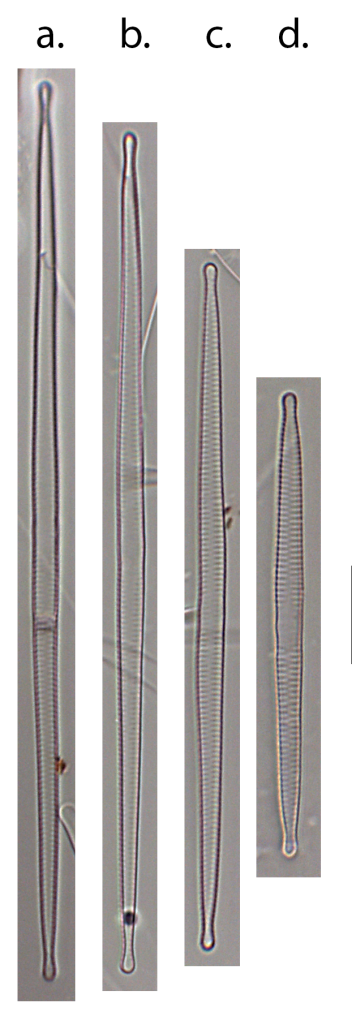

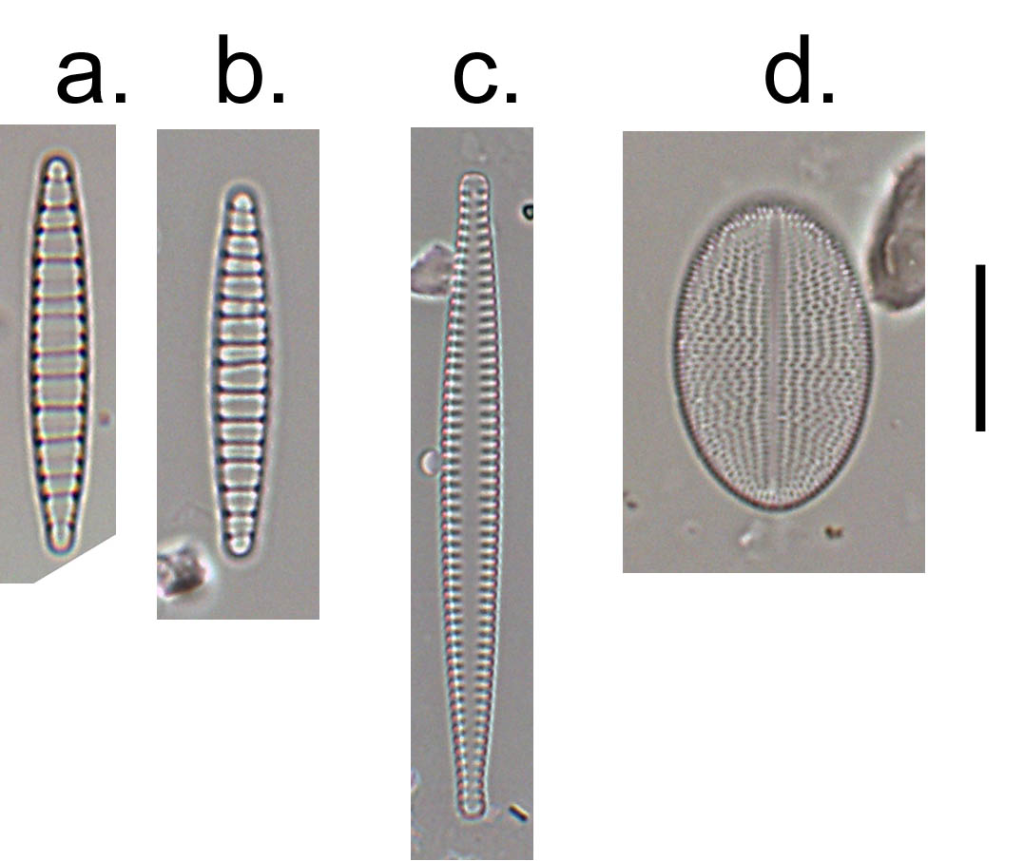

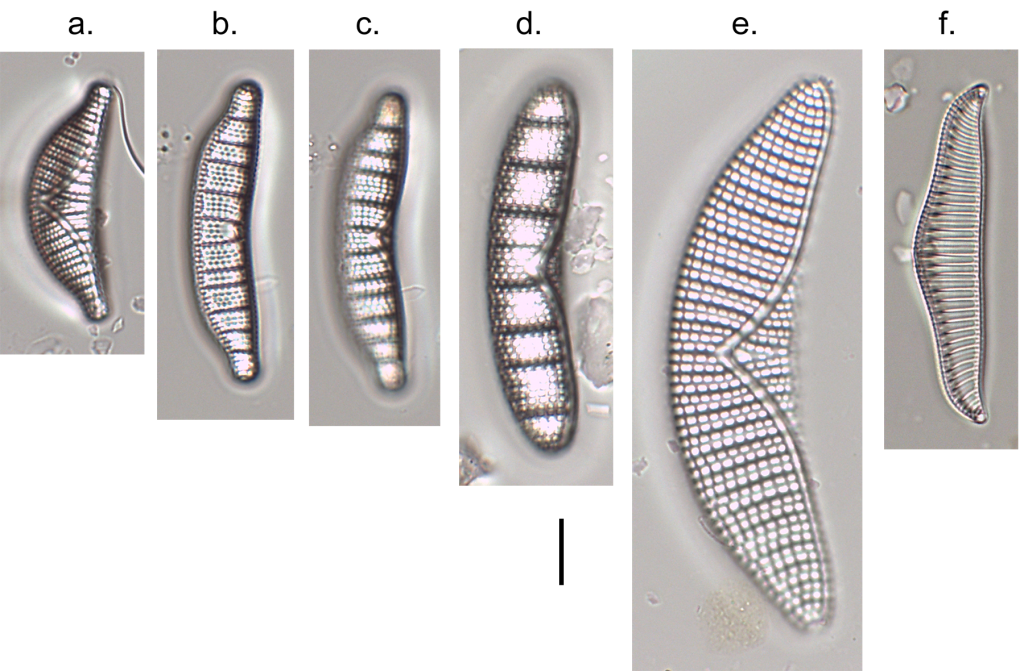

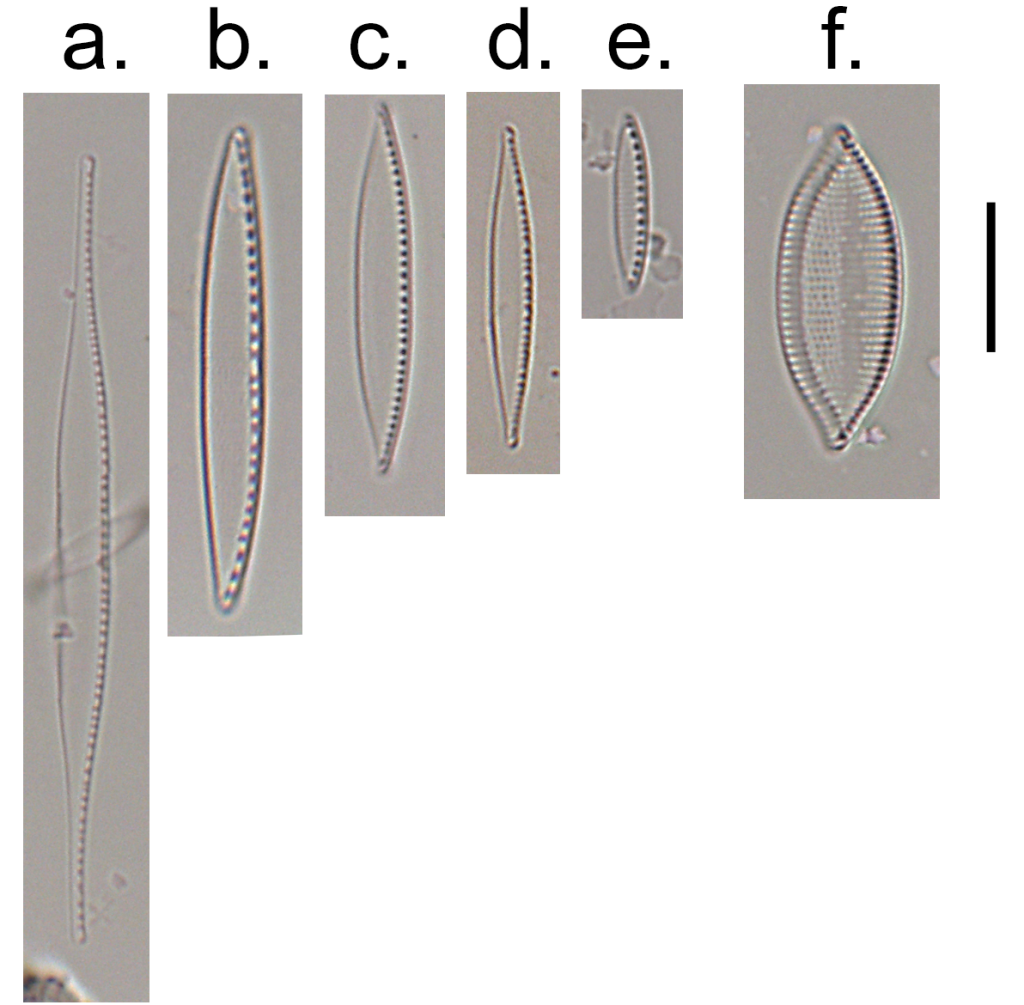

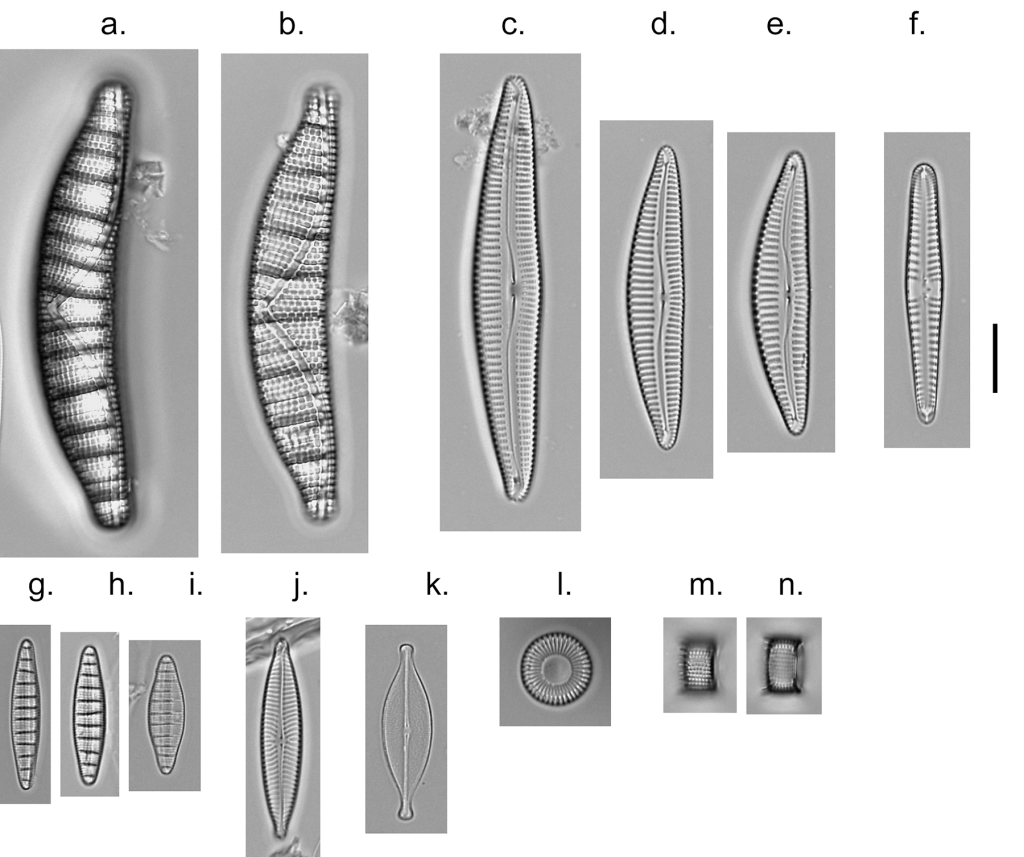

Gomphonema parvulum (top row) and Gomphonema calcifugum (bottom row), the two most common species of Gomphonema in Croasdale Beck (seen in the photograph at the top of the post)

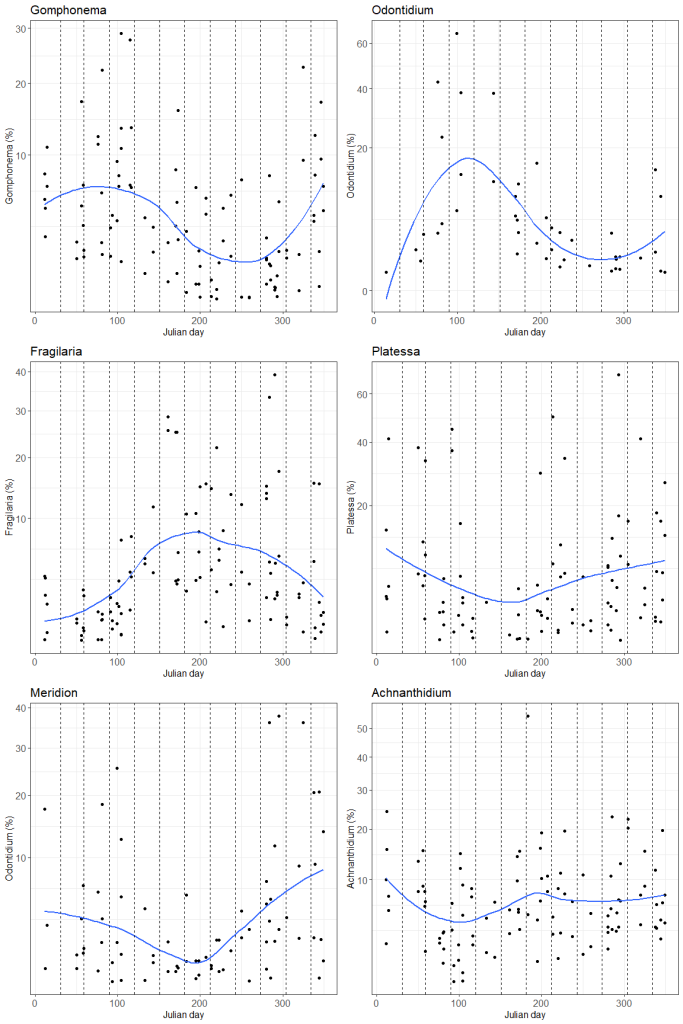

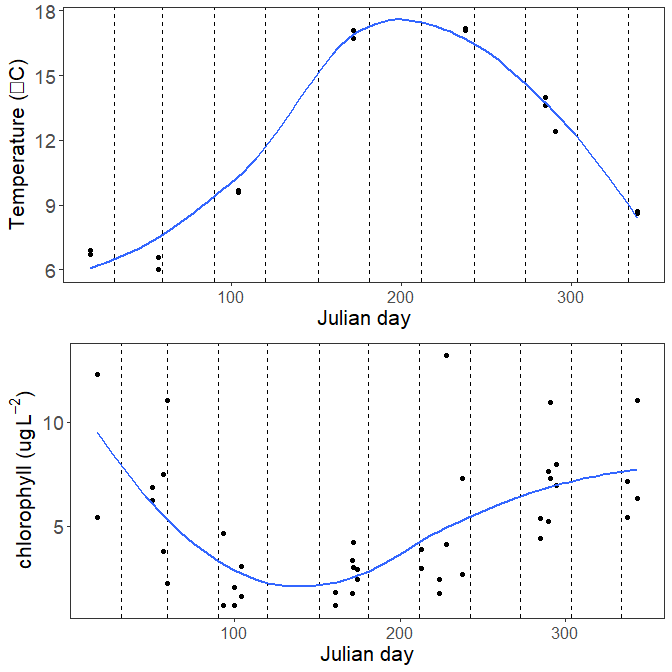

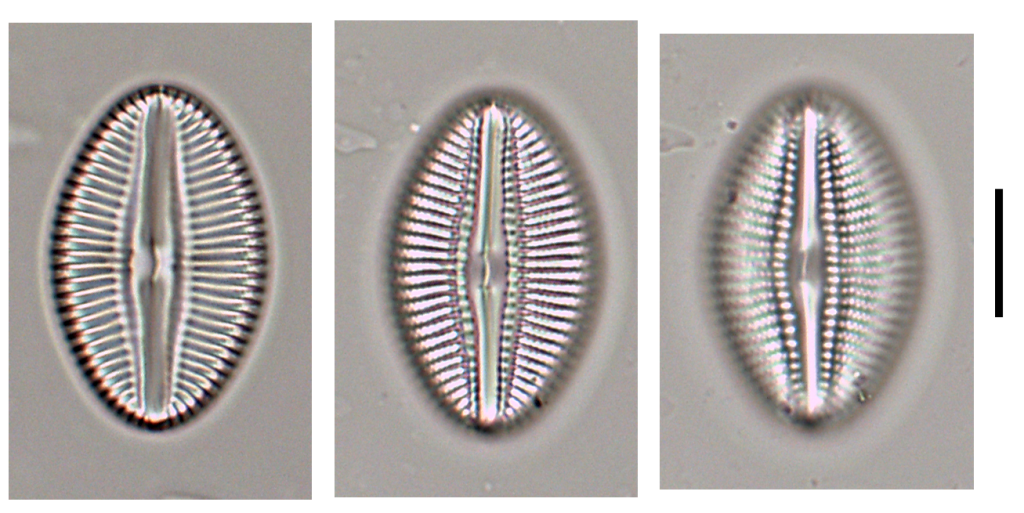

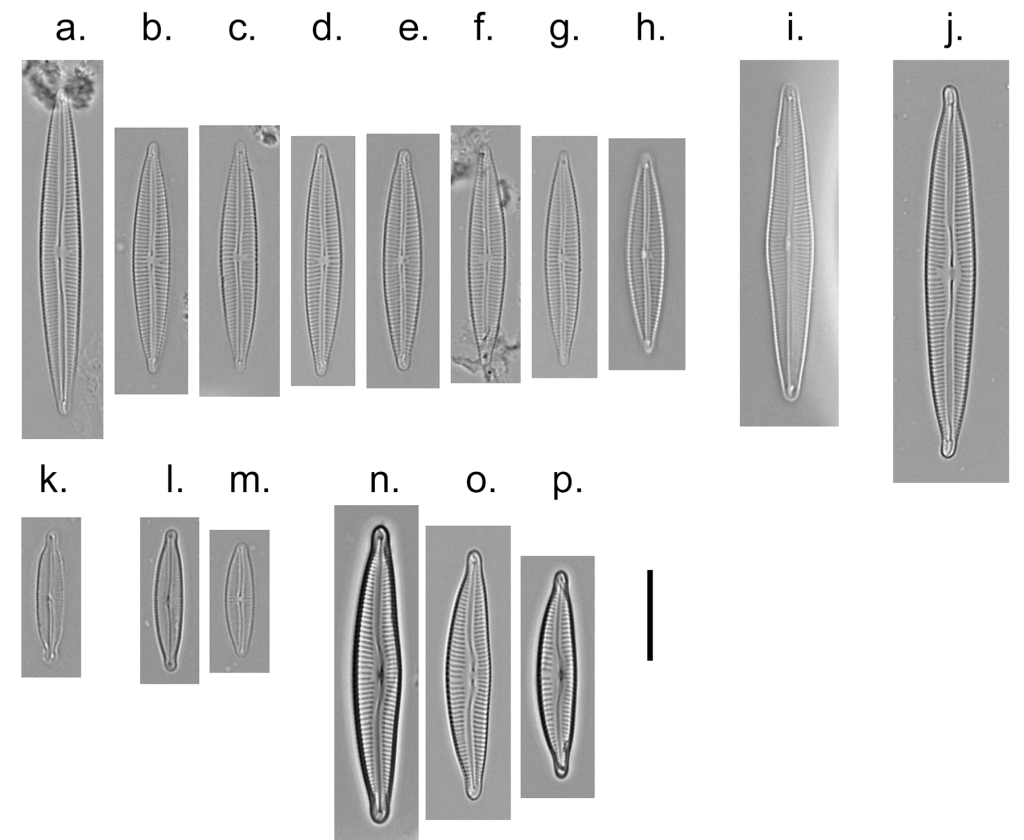

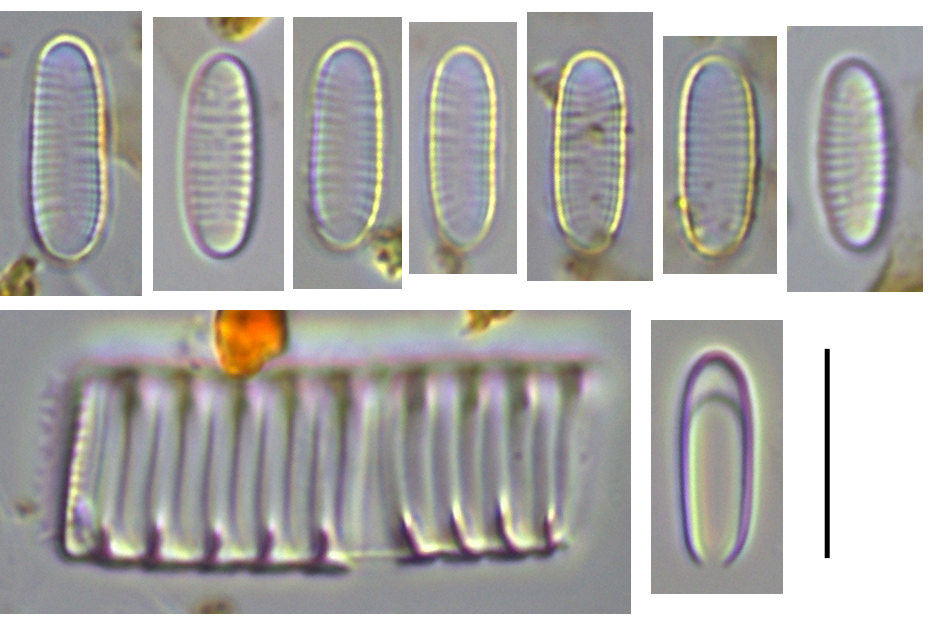

Both Gomphonema species in Croasdale are at their most abundant about now (just as in the River Irt). As March passes to April so a different diatom, Odontidium mesodon will become abundant and then, during the summer, it will be Fragilaria that dominates (at least two species – F. gracilis and F. novadensis) before, towards the end of the year, Meridion constrictum will become abundant. Platessa (P. saxonica and P. oblongella) show a weaker trend, with dropping to minima in mid-summer before rising again, whilst Achnanthidium shows no annual trend at all.

Annual trends in relative proportions of six common diatom genera in Croasdale Beck. Vertical lines divide the year into 12 months.

The diatoms are, in other words, behaving just as the terrestrial vegetation. Outside my window I can see crocuses where, a few weeks ago, I would have seen snowdrops. Daffodils are also beginning to appear. In nearby woodlands, I can see celandine, but this will soon be replaced by wood anenomes, bluebells and then wild garlic. The processes that drive these changes in higher plants are hard-wired into the genomes. We know much less about the reasons for changes in stream diatoms. Maria Snell made a convincing case for seasonal changes in diatoms in a stream on the other side of Cumbria being the result of changes in nutrient supply. However, I think it unlikely that Croasdale Beck experiences the same scale of nutrient flux. We know that the rise and fall of Asterionella formosa (another late winter/spring diatom) in Cumbrian lakes is a much more nuanced story, with temperature playing a key role and there is no reason to assume that the same does not apply to stream diatoms too. Nutrients will certainly be part of this tale, but there is a richer cast of characters than this simplistic interpretation allows.

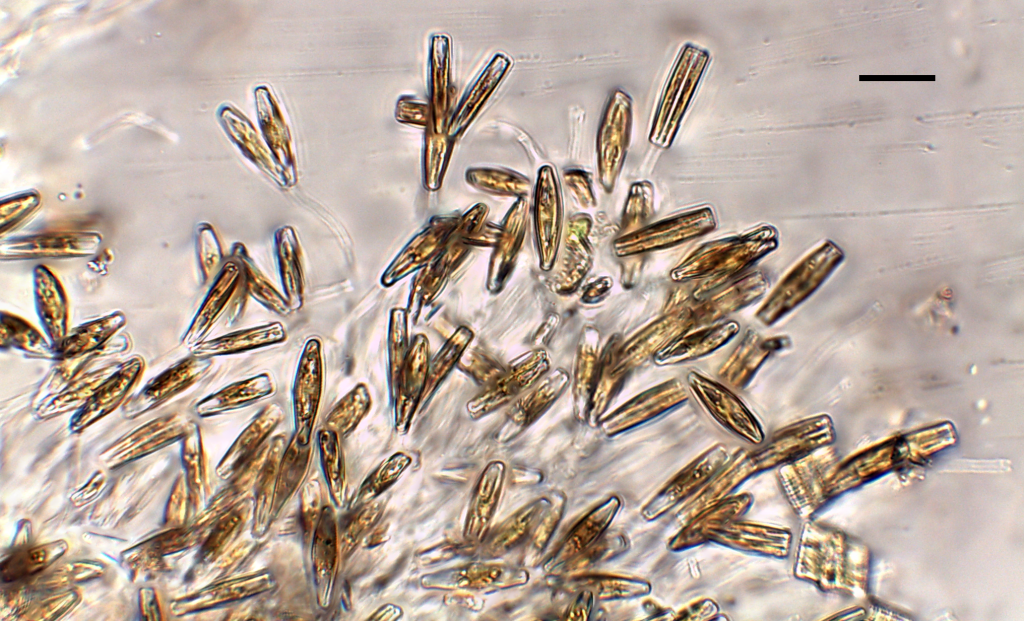

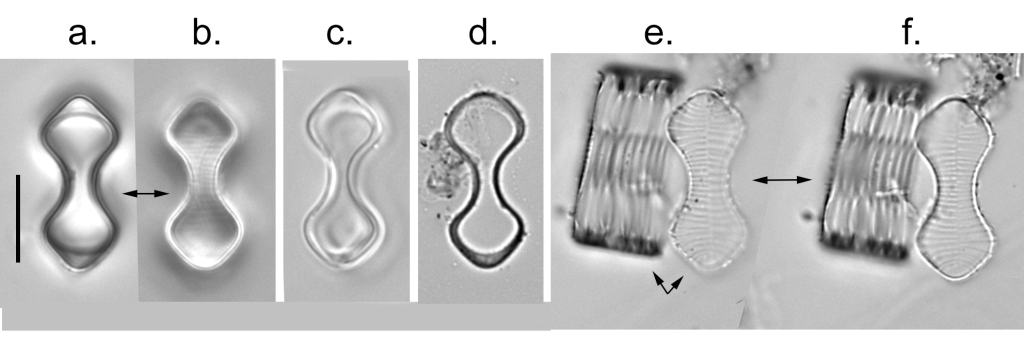

Cobbles from Croasdale Beck in February 2023, their upper surfaces glistening with a thick film of diatoms.

Why is seasonality in stream diatoms overlooked? One possible reason is that most sampling frequencies are too low to detect patterns within individual streams. Another, however, is that diatomists are not primed to look for this type of pattern. The Freshwater Benthic Diatoms of Central Europe, the one-volume handbook that many of us use, describes over 800 common species, and includes ecological and habitat notes for all of these. However, there is not a single comment on seasonality. By contrast, preferences for chemical water quality are described in detail. A benign explanation may be that seasonal preferences vary around Europe, but it is also possible that seasonality in diatoms is widely overlooked. The two reasons – not being told to expect seasonal patterns and not sampling consistently at the same sites with sufficient frequency – are intertwined.

It is the inverse of Newton’s famous statement, “if I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”. What if those we thought of as “giants” were actually, themselves, only dwarves? Maybe there are more patterns under our noses that earlier generations of diatomists had overlooked but which are ripe for a new generation to discover? Wouldn’t science be boring if everything the “giants” of earlier generations told us turned out to be true and there was nothing left for us to discover?

References

Maberly, S. C., Hurley, M. A., Butterwick, C., Corry, J. E., Heaney, S. I., Irish, A. E., … & Roscoe, J. V. (1994). The rise and fall of Asterionella formosa in the South Basin of Windermere: analysis of a 45‐year series of data. Freshwater Biology 31: 19-34.

Snell, M. A., Barker, P. A., Surridge, B. W. J., Benskin, C. M. H., Barber, N., Reaney, S. M., … & Haygarth, P. M. (2019). Strong and recurring seasonality revealed within stream diatom assemblages. Scientific Reports 9: 3313.

* All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely Players,

They have their exits and their entrances ….

William Shakespeare, As You Like It Act 2 Scene 7

Some other highlights from this week:

Wrote this whilst listening to: Lynyrd Skynyrd (pronounced ‘lēh-‘nērd ‘skin-‘nērd) following the death of their guitarist Gary Rossington. I’ve long been uncomfortable about a band that performed with the Confederate flag as a backdrop. It raises similar issues for me as the film Tár, about the extent to which it is possible to separate an artist’s views from their work. This week, however, I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt …

Currently reading: Lessons, by Ian McKewen

Cultural highlight: Fergus McCreadie Trio at the Sage, Gateshead although, to be honest, I’m still on a high after the Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum

Culinary highlight: Slightly belated shout-out for Gertrude’s Restaurant and Bar in Amsterdam where we ate and drank last week. “Small plates” and a bottle of an Alsatian Orange Gewürztraminer.

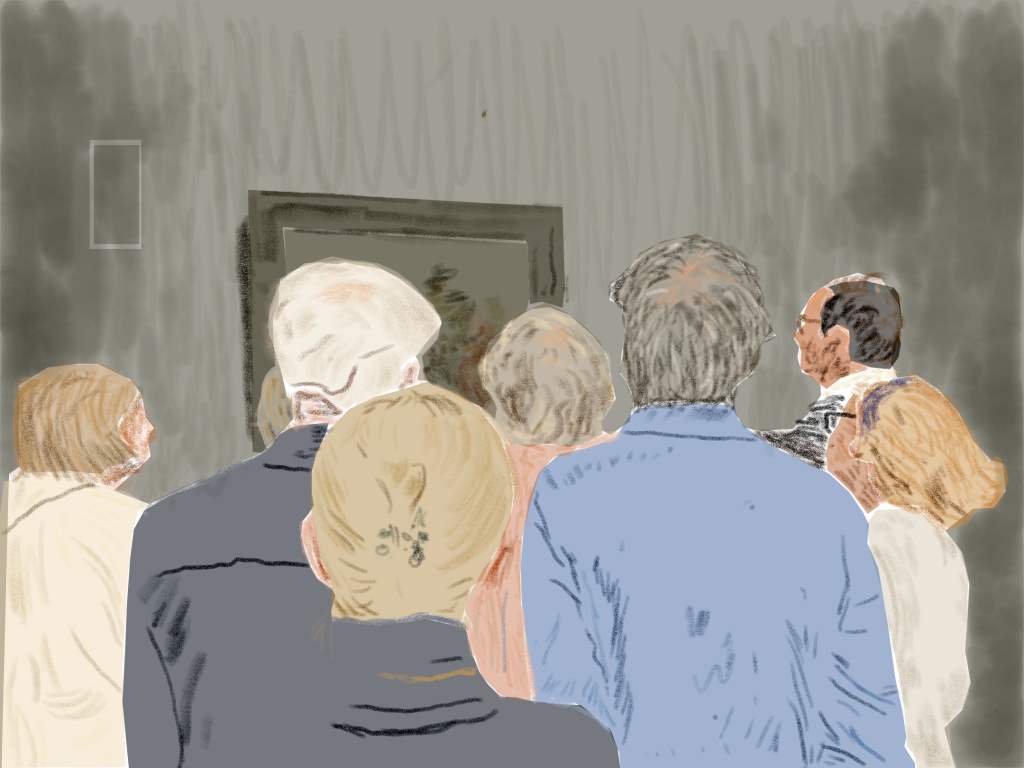

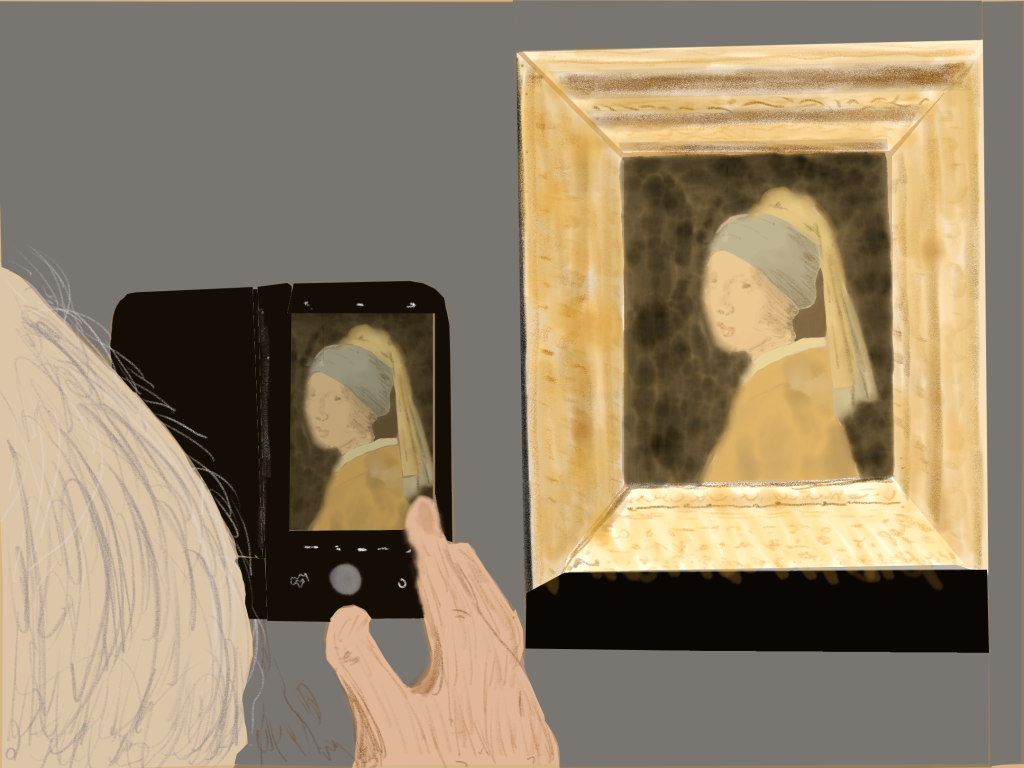

And finally, two sketches made on my iPad after the Vermeer show. My disappointment is that Vermeer’s “The Art of Painting” was too fragile to travel from Vienna. Otherwise, I could have drawn someone photographing a painting of someone painting someone. I had to make do with drawing someone photographing a painting of someone.